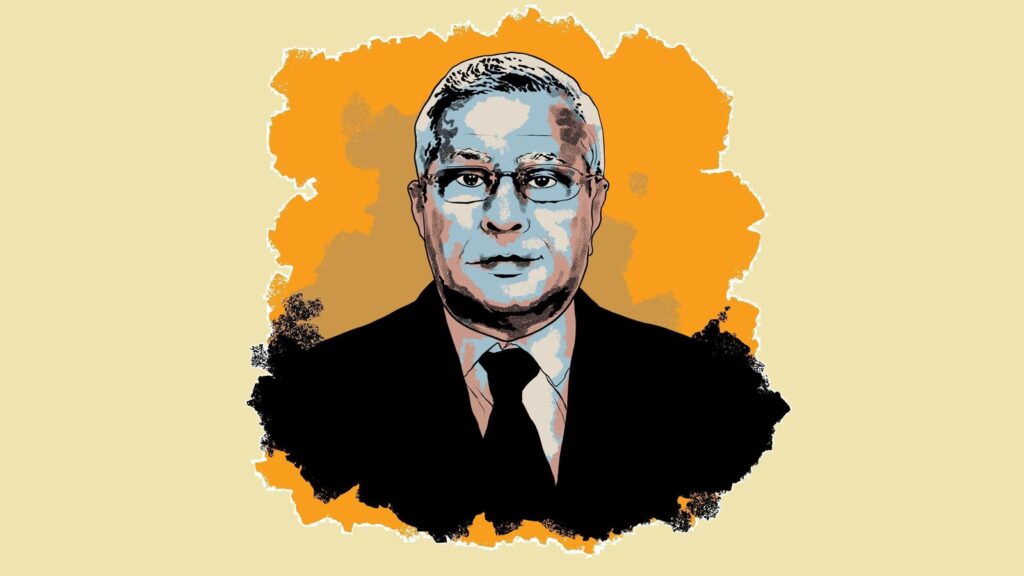

Bijon Nag, the entrepreneur who personified what Bengal could have been

Bengal has for many decades failed to produce the kind of entrepreneurship that was once its hallmark as the heartbeat of Indian business. With the exception of men such as Sanjiv Goenka and Purnendu Chatterjee, there have been few noteworthy successors to such legendary businessmen as Dwarkanath Tagore, Ramdulal Sarkar, R N Mookerjee and Alamohan Das.

There was a time when Kolkata (then still called Calcutta) was the commercial centre of India. The city’s port, strategically located on the Hooghly River to provide direct access to the Bay of Bengal and beyond, handled a wide range of exports including jute, tea, rice, spices and manufactured goods. With a strong communist movement sweeping through the state’s politics in the 1960s, Kolkata lost its way, and for many decades now its startup ecosystem has been relatively barren. Today, it is the only one of India’s largest metros by GDP that doesn’t boast of a single unicorn.

Of course, even through these bleak times there have been men and women who have tried to defy the odds and give wing to their entrepreneurial dreams in the City of Joy. One such man was Bijon Bhushan Nag, who passed away at a hospital in Singapore in January at the age of 82.

An idea is born

The founder of IFB Industries and IFB Agro Industries, Nag is credited with introducing fine blanking technology (a precision metal forming process crucial for producing high-accuracy and intricately shaped sheet metal components) to India. In the process he established IFB as one of the country’s leading white-goods brands. His big idea was to capture the share of the kitchen wallet of housewives, which is why the company also launched refrigerators, dishwashers and microwave ovens. In a delightful piece of innovation, the microwave came with a rich cookbook of recipes that would go on to acquire a life of its own.

Also read | Chairing Tata: How RNT set the leadership benchmark for his successors

Nag, a mechanical engineer whose stints in Germany and Switzerland taught him the value of precision and quality, wanted to bring these values to India. With that in mind he started Indian Fine Blanks Limited (IFBL) in 1974, in collaboration with Heinrich Schmid AG of Switzerland. In 1989 IFB Industries formed a joint venture with Bosch-Siemens Hausgerate to produce fully automatic washing machines and other home appliances. The JV wasn’t very successful, but IFB absorbed the technology sufficiently well to produce top-class appliances such as washing machines on its own.

Soon, he set up a machine tools plant in West Bengal, a first in the troubled state, and also bought and revived two sick tea gardens for his agro-based chemicals unit. Wisely, he expanded beyond Bengal, setting up a plant in Bengaluru to make seating systems and seat recliners for Maruti cars, and another in Goa for washing machines.

Politics – the good, the bad and the ugly

His best years, though, coincided with the 23-year-long reign as chief minister of Jyoti Basu, with whom he shared a family relationship. That relationship may have helped keep the company free of labour trouble – the bane of most other industrial units in the state. But by 1997, financial problems thanks to some thoughtless expansion and diversification became a real threat, with one major lender, IDBI, imposing stringent conditions on the company.

Also read | Jagannath Nana Shankarshet: A forgotten visionary amidst colonial chaos

Market rumours suggested a political rivalry was behind the company’s woes, which also included the creation of two powerful and recalcitrant unions – a curious thing, considering Nag had enjoyed a warm relationship with the workers for many years. Once, seeing the chairman ride a taxi to work, the workers pooled in money to buy him a car.

All these issues took a heavy toll on the company’s performance and in July 2004, IFB Industries was declared a sick industrial undertaking by the Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (the forerunner of the current insolvency and bankruptcy regime).

Quality shines through

But IFB had earned its spurs thanks to its product quality and its customer service. Sales and profits soon returned, and following a 2009 agreement with its creditors involving an interest waiver and equity infusion by the promoters, it emerged debt-free. By then Nag’s son Bikramjit Nag had joined the business, and the upswing in the company’s fortunes owed much to his managerial capabilities.

Also read | Sumantra Ghoshal: The Euroguru who warned of workplace dissonance

Bijon Nag built a fine business, and though it ran into trouble, only some of it was of his own making. His true love, however, may have well been storytelling. A fine raconteur, he loved a good tale and often explained his business moves with the same diligence as a carefully crafted anecdote.

Like any Bengali worth his salt he loved his macher jhol (fish curry). He also loved to feed visitors, often at his company’s unostentatious guest houses in various cities, where the pride of place was always given to the kitchen and cook. Not for him were the impersonal luxuries of five-star hotels. At heart he was a simple man who needed few luxuries and had little use for his personal wealth. IFB, the company he set up, offers a hint of the promise that Bengal once held out – and that has sadly remained unfulfilled.