The changing pecking order in semiconductors

NEW DELHI

:

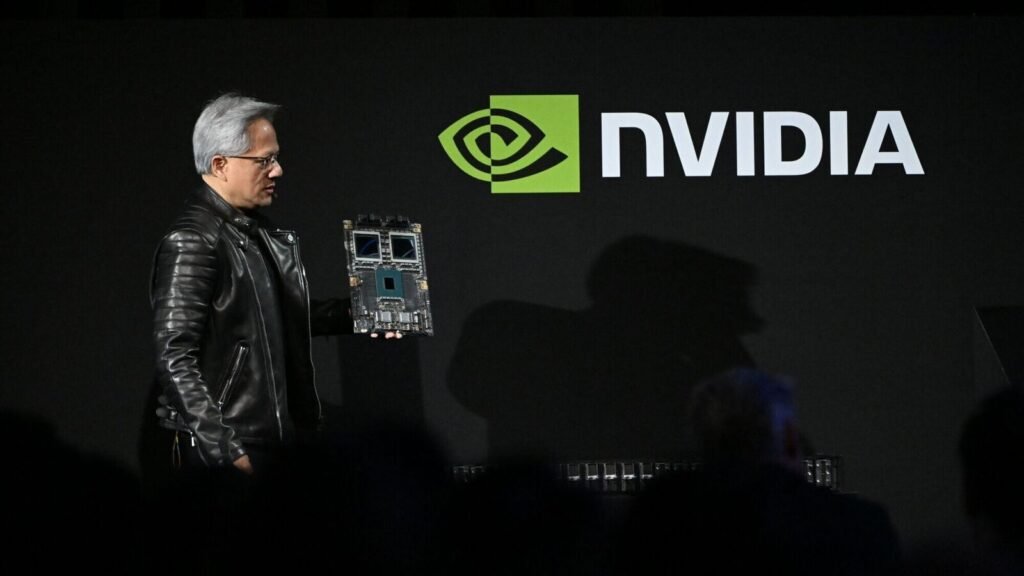

Last week, Nvidia Corp., the world’s largest artificial intelligence (AI) chipmaker, replaced Intel Corp., best known for computer processors, in the 30-share American benchmark share index. This movement in the Dow Jones Industrial Average reflects the big changes in the industry over the past few years, as AI took centre stage and the fortunes of top players reversed.

Nvidia’s market value jumped from about $81 billion at the end of 2018 to $3.6 trillion now, making it the world’s most-valued company, ahead of Apple Inc., Microsoft Corp. and Google Llc. Intel’s dropped from $212 billion to $113 billion.

In the last four fiscal years, Nvidia’s revenues jumped 265%, driven by demand for its graphics processing units (GPUs) used in AI applications, particularly large language models (LLMs) that dominate AI.

Meanwhile, Intel’s revenues shrank 30% during the period as Advanced Micro Devices, Inc., or AMD, ate away its dominance in the personal computer market. Intel’s decline was also due to other strategic mistakes, including turning down an opportunity to own 15% of OpenAI. The once dominant firm now faces the question of whether it can regain its footing alone or become a part of Qualcomm Inc., which has approached it for a potential buyout.

Nvidia’s surge and Intel’s decline have also impacted the broader supply chain. Unlike Intel, which is an integrated device manufacturer and handles all aspects of semiconductor production, Nvidia outsources manufacturing, benefiting foundries like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. Ltd, or TSMC. TSMC has become the primary manufacturer of the company’s AI-focussed chips, taking its market cap to over $1 trillion from $191 billion at the end of 2018.

Shortage-glut cycle

While AI is a key driver of these changes, some of its causes can be traced back to the covid-19 pandemic, when remote work mandates and higher reliance on digital devices pushed the demand for electronics, causing a shortage of semiconductors. The median inventory of semiconductor products dropped from 40 days in 2019 to less than five days in 2021, the US commerce department noted then.

However, as the pandemic’s effects waned and demand for electronics softened, the semiconductor industry went from shortage to surplus. The glut shrank industry revenues across the value chain, including equipment manufacturers like ASML Holding NV, which supplies essential tools for chipmaking. Global industry sales dropped 8% to $526.8 billion in 2023, according to the World Semiconductor Trade Statistics (WSTS). All these added to Intel’s woes, which was already facing a slew of issues, including manufacturing slip-ups, that allowed its rival AMD to increase share in its core personal computer market.

Geopolitical concerns

Shortages and gluts are common in the industry because of cyclical demand and long production lead times. However, the shortage-glut cycle the industry experienced in the 2020-2023 period highlighted vulnerabilities in the supply chain, pushing many countries to invest in building domestic capacity. Europe and South Korea plan to more than double, and the US triple, their WSPM (wafer starts per month) capacity in the 2022-2032 period, according to the latest state of the industry report by the Semiconductor Industry Association.

As global capacity goes up, it has also raised the question of how long AI-driven demand will last and whether it will change the pecking order again. While it could happen eventually, there are other immediate concerns. In a September report, Bain & Co. Inc. argued that the industry could face a shortage yet again, triggered by AI-driven demand for GPUs and AI-enabled devices.

Global competition

Along with chip demand and supply, the industry is also being shaped by national ambitions and geopolitical concerns. India’s offer of financial incentives to chipmakers is a part of its plan to become a high-tech manufacturing powerhouse. Similarly, the US CHIPS Act aims to revitalize semiconductor manufacturing in the US. This, in turn, could help Intel regain some of its competitiveness. Intel has already received $8.5 billion in grants and up to $11 billion in loans to support its plan to spend $100 billion over five years in building and expanding chip factories in the US.

However, it’s unclear how Donald Trump’s election will impact the CHIPS Act. During his campaign, Trump criticized the Act’s cost and called it a “bad deal”. His focus is more on imposing tariffs than on providing subsidies. While it’s unlikely he will roll the legislation back, some changes might be afoot, and that again could impact the industry landscape.

www.howindialives.com is a database and search engine for public data.