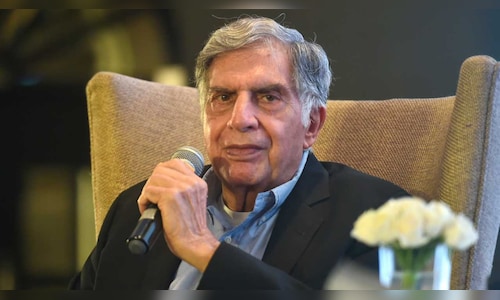

Interview | Ratan Tata-A Life: A glimpse into the childhood, challenges, and triumphs of an Indian icon

The biography, Ratan Tata – A Life, explores this remarkable journey from his isolated childhood through his first position within the Tata Group to his transformative tenure as chairman of Tata Sons. It uncovers lesser-known facets of his life, such as the obstacles he faced in school, his early career as an architect, and his first serious relationship.

Written by retired bureaucrat Thomas Matthew, who first crossed paths with Tata nearly 30 years ago, the biography was inspired by Matthew’s 2018 decision to chronicle Tata’s life. With insights from over 130 interviews, capturing stories from people touched by Tata’s influence, Matthew offers a comprehensive look at the man behind the legacy. To delve deeper into these untold stories, CNBC-TV18 spoke to author Thomas Matthew.

Below is the verbatim transcript of the interview.

Q: You have known Ratan Tata going back three decades. It was in 2018 that you decided to put this down in words. Why?

Matthew: It’s not me who decided. It’s by chance. In 2017, he came to Rashtrapati Bhavan as the distinguished invitee of our President Pranab Mukherjee. He was there for almost two days. And we spent a lot of time together. We got socially close.

I’ve been meeting him very frequently since 1994, many times. He used to come at the Ministry of Finance as a member of the captains of industry. In 2017, we spent a lot of time together. Then I was in Mumbai along with my son, George, who’s in the Foreign Service. He said I want to see Ratan Tata. I want to see if he’s for real. I said, you just can’t go to him and see him. I picked up the phone and asked, sir, can I come and see you because my son is pestering me. He says he wants to see you in person and see if you’re the real Ratan. He said, come over for dinner if you have the time. That’s how humble he is. That’s his level of humility.

In the evening, we went. And for three hours, my son and he got chatting. And he gave us snapshots of his life, which I was overhearing. I found that exciting. I said, don’t you think you should write your autobiography? That spur of the moment, he turned around and said, I’m not going to write. If you want to write, you write my biography. And that’s how it started. It was music to my ears. I wanted to ask him a second time; did you say that? But I said, I’m not going to do that. I want to take the chance and run.

Then started the journey to unravel the complexity of the simplest man you can ever meet.

Q: You spent over 140 hours with Ratan Tata, interviewing him, probably much more than even his closest sort of colleagues and friends perhaps have spent. And what we know from public persona, public perception, is the man who came in, who sort of brought together this very diverse and disparate conglomerate and made it a cohesive whole. But what, to your mind, has been the most standout success of Ratan Tata?

Matthew: If you look at it from the business point of view, let me tell you, he became chairman in 1991, March 25. That was a time when there was also this policy of Narasimha Rao, the Manmohan Singh government, to have economic liberalisation. He inherited from JRD, as you said, a disparate group of companies, piloted by equally capable stalwarts, not so favourably inclined towards Ratan Tata, and were very unhappy that Ratan was chosen as the chairman.

Many others thought that they were the best to be the chairman. But for several reasons, Ratan was chosen. And it is not because Ratan was a Tata, not that because he had a surname, but he had this amazing vision, a scientific mind, courage, and as JRD said, an amazing memory like him. And said he was most suited, and especially his young age—52-53 years old is the right person to have a long tenure. And it’s extremely important—long tenure—because he will have to navigate the ship of Tata through the tumultuous phase of economic liberalisation and the transition. And therefore he became chairman.

Now, if you ask me, we probably researched, deep dived, and there is no piece of information, there’s no piece of anything written that we have not dug out. And he was very lonely in 1991 when he took over. He had the satraps working against him. But almost about three, four years before he stepped down, he said, when I took over, I didn’t have many friends. And people thought that I didn’t have the capability of JRD and that I would run the conglomerate down. But he proved them wrong, completely. What did he do? There’s something which is unknown, let me tell you. That’s because it is Ratan’s own fault. He was a very reticent man. He has not spoken about his own achievements. He brought together a conglomerate and made it like a federal government but with a unitary bias. That means you give them the freedom to work in actual unison with a common goal and don’t engage in internecine conflicts.

Q: But did he feel like he had accomplished this, what you believe is his most significant contribution to the House of Tata?

Matthew: You tell him that, sir, your achievements have been stupendous. The man would blush. It’s almost like a Greek god, the complexion he has. You continue with this compliment, and he’ll start biting his lips. He gets very nervous and embarrassed.

But there are many things which surprised him. Because let me tell you something, the much-vilified government is much better in record keeping. The stupendous changes, the enormity of the changes that he brought about in the group has not been mapped or recorded anywhere. See, you have about more than two dozen reports by Harvard University, the best of MBA institutes in the world. But they have only dealt with one or two components of his restructuring program, which I say, which according to me, has 11 caterpillar legs of growth. They only identified two or three.

Q: What are the other nine?

Matthew: The most interesting is the JRDQV Award. Then the Tata business model. Then you have TCOC, which is the Tata Code of Conduct. Then you have the GEC. Then you have the branding, that is the freedom to use the logo. Now, everybody’s talked about only JRDQV Award. But this man, what he did, he brought in the TCOC. And he brought in, again, the most important contribution. Let me tell you, like most of the people don’t talk about is that when he took over in 1991, you’ll be surprised to know that Tata Sons, the parent company or the holding company, had fewer shares in its flagship company called Tata Steel, at that time TISCO, less than what Birla’s held in TISCO.

So after 1991, Ratan came out and said, if we don’t merge, if we don’t increase our stakes, we are going to be eaten up by the multinationals. So he and his famous lieutenant NA Soonawala hit upon several innovative schemes by which they increased the stake of these companies. And through this mechanism, they brought in amazing cohesion.

There was a time when I surprised him. He took over as chairman of Tata Motors in 1988 and stepped down in 2012. Now, if you look at the percentage growth of the top line from 1988 to 2012, but actually it should go up to 2016. Now you’ll ask me why? Why 2016? That is because you look at a McKinsey report or any major report, after an economic contraction that happened in 2008, it takes you eight years for you to recover. Now, I mean, I’ll wager with anybody. I wagered with him. I asked him, sir, can you tell me what is the percentage top-line growth? He said, I don’t remember any of this. You know what? It kissed 20,000%. Will you believe it? He said, no, that’s not possible. Then I said, sir, give me a blank cheque. He said, that I won’t give you. So that’s it.

And I’ll give you another thing. This man has not been recognised. I don’t know if I should take an example, but that’s the example I’d like to take. You heard about Jack Welch, the so-called, you know, titan of GE. Yes. From 1981 to 2000, he was at the helm for about 19 years. He grew his company from $27 billion to $130 billion. And there you are talking about 361% odd. You know, when Ratan Tata took over, he had a turnover; that’s the top line of $5.4 billion. He took it to $100 billion which is 1742% increase. And the economist and fortune would dub Jack Welch as the biggest thing that has happened to industry in the world. Compared to him and the other industrial leaders, to me, Ratan Tata is the Shahenshah of industrial leaders. But nobody says it. He’s an Indian. So, therefore, people don’t recognise him. But the world, even a person like Henry Kissinger, has been talking about him in such glowing terms. I interviewed him and he said he’s like 2% of the best the world can ever give you. And he says the most important is that, for Ratan, it is not business proposal that will motivate him. Social responsibility has to be fulfilled. And the business proposition will make that happen. What a profound statement. There is so much to speak about this reticent man.

Q: 700 pages of stories there.

Matthew: And that is without notes.

Q: You said that he was a lonely man, especially in the early 90s, when he was going through this phase of restructuring and reformation. But what about the period, especially the Mistry period? What about the period after that? Did you have conversations about what he thought that had done to him personally in terms of reputation? And more importantly, what he believed the future would hold for the Tata Group post something like that?

Matthew: Ratan Tata is made out of a different mould. When he took the decision to replace Cyrus, he doesn’t like to use the word remove. He said he was replaced. Now, did he want to replace him? I’ve done extensive research and he really did not want to change him. So what did he do? He tried his best to bring in external elements who could help Cyrus Mistry rise to the occasion, and also change his strategy so that the Tata Group would be able to perform better, move along the trajectory, which he thought the corporation should move. But that did not happen, for many reasons. Therefore, he got Nitin Nohria, the Dean of Harvard, to help him. I did about six, seven hours of interview with Nitin Nohria. He said, there was only one intention of Ratan Tata to involve me in the group as a director, that is to help Cyrus understand the complexity of this group. That is because Mistry did not come with that kind of experience, which is required from salt to software to steel. It’s so complex. I mean, it’s almost like a nation, for all practical purposes. And he supported him. Somehow, for some reason, maybe Cyrus must have gotten influenced by the GEC, the General Executive Council. Interestingly, he employed or filled it with youngsters. But Tata is a very traditional organisation. And the GEC before the GEC of Mistry had stalwarts like JJ Irani and Krishna Kumar. The most interesting thing I did in analysis was that the average age of the GEC under Cyrus Mistry was less than the experience of the earliest stalwarts. Now, how can somebody with an age of 35, 36, talk to a veteran like JJ Irani? And that is a brilliant PhD from Sheffield. You can’t talk to him about Tata Steel. You need veterans to talk to veterans. But yet he tried, and he tried to support him. He gave him the full weight of Tata Trust behind him. I’m not saying this, a lot of journals have said that. But for some reason, he was not able to rise to the occasion. And that’s what Nitin Nohria told me, he said, there comes a time when you have to make a decision, whether you will fulfill your fiduciary relationship with the millions of stakeholders you have, and also fulfil the goals, which were enshrined by his forefathers in making the endowments to Tata Trust so that they can give back to society what they said should be done. So he said, do you take the painful decision because the performance of the corporation or companies is going down? So what will you do? Then he says he had to make the most painful decision. Now, did it cut both ways? I think, if you honestly ask me, it cut Mr. Tata much more than it cuts Cyrus Mistry. It upset him to no end.

There was a small subchapter which I changed in this book. After his retirement, he wanted to play the piano. In the corner, there was this piano. And there was a subchapter which I said, the piano goes silent. Then I removed it because, he did not like that. He did not like that subtitle, or, you know, the subchapter. Because it was showing him in his most agonising times. Believe me, some people outside do not know that it hurt the man who wielded the sword more than the person who was removed with the sword. That’s what it is. It’s a very sad story. And he always used to tell me, I feel very bad that I did not show him out the door like the Tata way. I couldn’t do that. And we don’t do this. We don’t replace people. But, as I told somebody else, it was his inevitable, regrettable moment. He couldn’t do anything but do it.

Q: As you pointed out, sometimes you do have to follow through on your fiduciary responsibility, which he thought that he was doing, even though it was a very difficult decision for him. But let’s talk a little bit about the man. Because, while there is this public persona, there’s very little that we know about him. Because he chose to stay away from the public glare, he chose to lead a very private life. But what we do know is that he had a deep commitment to the things that he was passionate about, whether it was his love for animals, or architecture, or, empathy. But, what was Ratan Tata, the man, really about? I mean, simple, generous sense of humour, a lot of people have said that. But you knew him in ways that many perhaps didn’t.

Matthew: He had a funny bone in him. He would play pranks. When he was a student in Cornell, what he used to do is he used to call a lot of his friends who had the courage to fly with him. He used to go up, switch off the engine, and say, engine is flamed out. And then, after about, maybe about 20 or 30 seconds, when they start screaming, he will switch on the engine.

Q: Was that really his first love?

Matthew: Flying was his first love. And always was. Even at the age of 80, 85, you show the man, who may not be able to stand directly immediately, show him an F16, he will jump up and say, you get me my jacket, let me go fly that. That is passion.

In the US at the time, you could only send $180 a month. That’s what he got from home. And he had to pay for his flying classes. He pushed aircraft, he cleaned them, and then he also sold his cufflinks. So he says, at times it got insulting.

Q: He sold his cufflinks—Ratan Tata?

Matthew: Yes. What else could he do because RBI would not allow you to send money to the United States. He had a funny bone, and then he’ll make fun of you, and he used to mimic Henry Kissinger.

Q: He was a good mimic?

Matthew: You can’t imagine; he was a great mimic. His sisters, he loved them dearly. They used to be at the receiving end of his, funny character. And he’s very simple, except for the suit he wore. That’s because if anybody saw him more than six feet, glowing complexion, a thick crop of hair, and very polite. And, you know, he could actually melt any heart. Men or women. And then he’s so simple.

I must have had hundreds of lunches at his place. And, you know, from where do we get the lunch? Taj? No. Across Halekai, there is a post office, on the right side, there is a dirty fast-food shop. And they give you bad French fries, but good Pizza and Coke—that’s what we used to have.

Q: Let’s talk a little bit about the legacy that he thought that he was leaving behind. And I remember in an interview that we did with him, he said, I would want to be remembered for being someone who did my best and left the group in a much stronger place than I had inherited. As he looked ahead what was his aspiration?

Matthew: He had this famous annual general manic meeting or the AGMM, as he would call it. In the AGMM towards the end, he said, by 2022, I want the top line, to go to $500 billion. But that kind of vertiginous growth will take a different kind of leadership. At present, I think it’s going well, but under Cyrus it had slowed down. Did he leave a very strong organisation? He did. And most importantly, I mean, I think one of his greatest achievements, it may be sacrilegious to say that, in my assessment that I’ve stated, I’ve got a subchapter called Connecting Centuries, and I’ve said, just as Jamsetji brought the Tatas to the country, Ratan brought Tatas to the world and making the group more popular among a larger section of the society when you look at it globally. Therefore, in a manner of speaking, it may be very difficult for the old Tata veterans to accept. I will put Ratan Tata maybe a little above any other Tata.

Q: That’s quite a statement.

Matthew: I can defend it. Ratan Tata was not a man who will boast. In Cornell, he said, my foreign acquisitions were “like the empire striking back.” I love that because he’s a very deeply patriotic man. And the patriotism came out. From 2004 to 2012, and when he stepped down, 60% of the top line came from abroad. And let’s look at it differently. From the queen to the cognoscenti in the UK, to all the people who matter, they love Jaguar Land Rover and they use it. Let’s go back for a minute. Largest manufacturing employer in the UK. When a Britisher wakes up, imagine they used to be our colonial masters. When they wake up, their morning cheer is brought by the three Ts, what I call it. What are the three Ts? Tata Tetley Tea. And when they get up and go out, if they are rich, if they travel in a Jaguar, it’s owned by the Tatas. And even if they don’t, if they take a tram, the steel is made by Corus. The New York Times in 2007 made a fantastic statement. When Corus was acquired, the entire nation erupted with joy and a new sense of nationalism prevailed. And the sense of nationalistic goal Ratan Tata embedded in that acquisition was amazing. And, the New York Times said after that—India is known for its Maharajas and elephants. Soon India will be known for the Tatas.